Could a bacteria in yogurt diagnose diseases?

By Katie Guzzetta, PhD

Microbes are arguably our closest companions throughout life. They help us digest our food, release nutrients we are otherwise unable to breakdown, train our immune system, and can even influence the brain! But what if gut microbes could be more than a silent life partner? What if we can reprogram microbes to diagnose diseases within our gut? Enter “Record-seq.”

Setting the stage

Cells are constantly monitoring and reacting to their environment and metabolic needs, such as acid stress or nutrient scarcity. Therefore, in every cell, gene expression (the process where information from a gene is used to create a functional product, like a protein) is highly dynamic.

Currently, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is the gold standard for measuring gene expression. With RNA-seq, we essentially capture a photograph of all the gene activity within a cell at a given time. However, to achieve this, cells must be collected at a specific time and from the specific location of interest, then broken open to retrieve RNA. Therefore, it is impossible to perform RNA-seq multiple times on the same cell, limiting us to a one-time snapshot of a cell’s gene expression.

These features of RNA-seq make it challenging to capture short-lived changes in gene expression, as well as disentangle culminative molecular changes progressing over time, such as in diseases. Moreover, hard-to-access regions, like the gastrointestinal tract, pose another challenge, and we currently rely on highly invasive procedures, such as endoscopy, to access them.

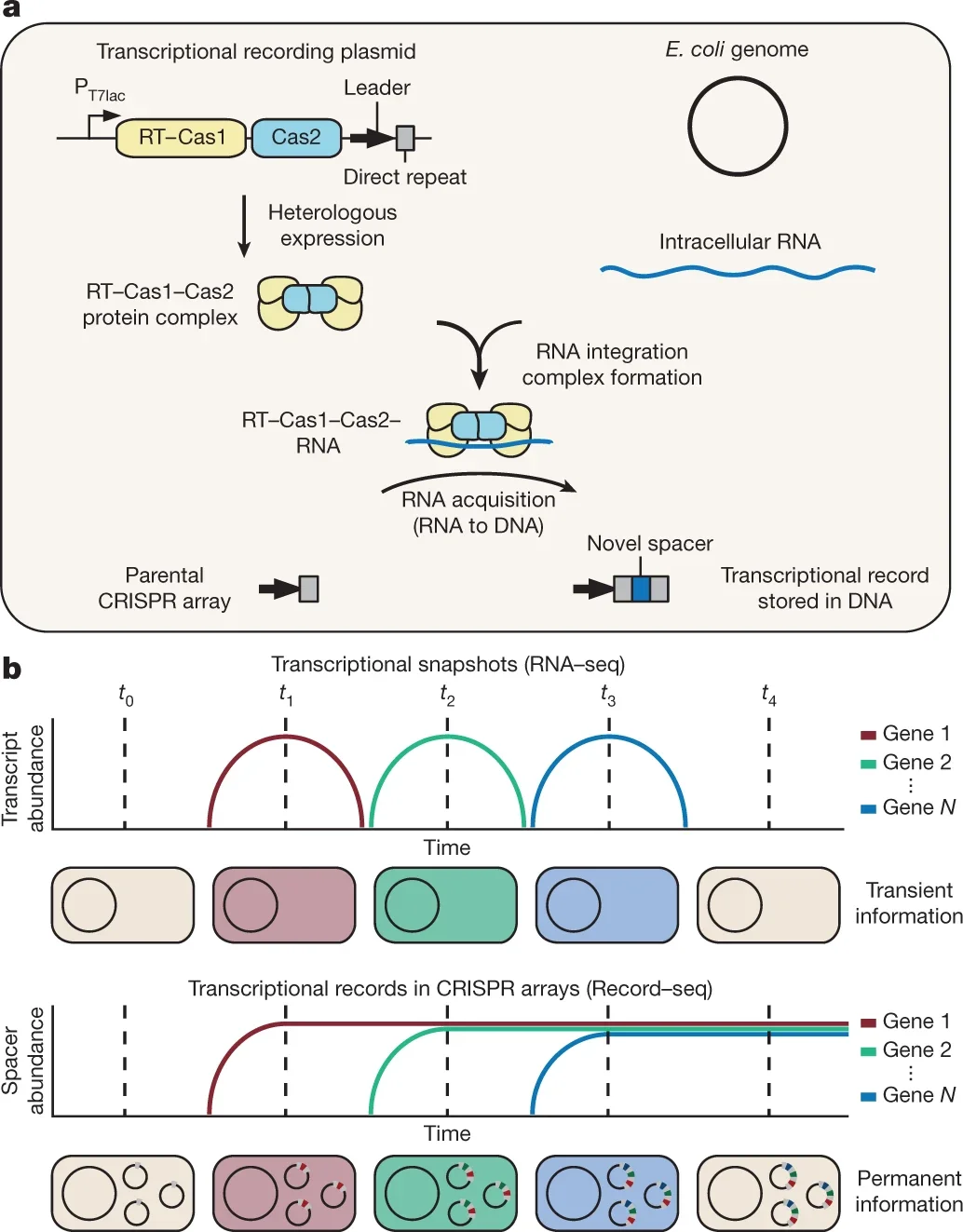

To address this, we have designed a way to capture RNA and permanently store it chronologically within a cell’s stable DNA. In this way, we can essentially record what genes a cell is expressing over time, turning what was previously just a cellular photograph (RNA-seq) into essentially a video recording (Record-seq), which we can use to noninvasively monitor hard-to-access places over time, such as the gut.

Figure 1: RNA-seq captures transcriptional information at one timepoint, while Record-seq captures and retains transcriptional history over time. Figure from Schmidt et al. (2018) Nature.

How does Record-seq work?

Record-seq repurposes components of bacteria’s native immune system, CRISPR, which records snippets of infectious viral DNA into bacteria’s genome, creating a cellular memory for fighting future viral infections. Rather than capturing foreign DNA, Record-seq utilizes an adapted enzyme complex “Reverse Transcriptase-Cas1-Cas2” to acquire bacteria’s own RNA and reverse transcribe this into a specific section of the cell’s DNA, where it is stably stored (1, 2).

This process creates a chronological record of bacteria’s gene expression that can simply be sequenced to read out a cell population’s transcriptional history.

What can we do with Record-seq?

Record-seq captures a transcriptome-wide memory of a bacteria’s activity over time and is currently established in Escherichia coli (commonly known as E. coli). With Record-seq, we can detect when a population of cells has been exposed to the herbicide paraquat, even if the cells were exposed only briefly1. Record-seq can also pick up on cellular responses to oxidative stress and acid stress1. The possibilities of detection seem endless, as long as the sentinel recording bacterial strain can respond to the stimuli of interest.

The most impactful work using Record-seq has involved deploying these sentinel bacteria to study the mouse gastrointestinal tract. By orally administering these bacteria to mice and collecting fecal material, Record-seq has been used to non-invasively detect and record gene expression history of bacteria as they travel through the digestive tract, providing insights into otherwise inaccessible environments. Crucially, Record-seq has demonstrated it can detect and differentiate mice on different diets, even after their diets have been changed, and captures unique signatures of inflammation in a mouse model of inflammatory bowel disease. This highlights Record-seq’s potential as a non-invasive diagnostic for dynamic conditions within the gut.

What limitations does Record-seq have?

With Record-seq, we essentially see through the eyes of our bacteria. We have access to the memory of our sentinel bacterial cells but are therefore also limited to our strain’s biology and how well we understand their genes’ functions. Record-seq is established in E. coli, the most commonly used lab bacteria, which has a large genetic engineering toolbox and a highly described genome. These features, coupled with the fact that E. coli is native within the gut microbiome (one strain of E. coli called “Nissle 1917” is even considered probiotic4!) provides an excellent foundational host bacteria for Record-seq. However, the gut microbiome is highly diverse, and expanding Record-seq to other diverse bacterial strains that have other metabolic abilities could allow us to better understand specific features of microbe-host crosstalk, such as fiber degradation or even pathogenesis.

Figure 2: Recording in the gnotobiotic mouse gut can report on intestinal inflammation, diet, and microbial cross-talk! Figure from Schmidt et al. (2022) Science.

For microbial diagnostics to be used in the clinic, safety is of top importance! A series of clinical trials first would need to be conducted to define the appropriate bacterial dosage and clinical efficacy. Additionally, genetically engineered material must be contained so that it does not leak into the environment. This can be achieved through auxotrophy, wherein bacteria are engineered to rely on a specific metabolite that does not exist outside of the body. This approach has been used by Synlogic in their development of a bacteria engineered to treat the rare disease phenylketonuria (PKU)5, and has gone through Phase 1 and Phase 2 clinical trials. Additionally, engineered bacteria face a lack of regulatory framework, making it difficult to predict how they will be perceived by regulatory agencies.

The future of microbe-based diagnostics

Wouldn’t it be nice to simply eat a yogurt, give a little poo sample, and have access to a wealth of information about the health of your gut? Inflammation, nutrient abundance and absorption, pathogenic bacteria, or maybe even early signs of cancerous polyps – the potential applications for microbial diagnostics in the gut are immense. Though Record-seq is not ready for clinical use yet, we are actively making progress to establish engineered bacteria as the ultimate non-invasive diagnostic tools.

References

Schmidt F, Cherepkova MY, Platt RJ. Transcriptional recording by CRISPR spacer acquisition from RNA. Nature. 2018; 562(7727):380-385.

Tanna T, Schmidt F, Cherepkova MY, Okoniewski M, Platt RJ. Nature Protocols. 2020; 15(2):513-539.

Schmidt F, Zimmermann J, Tanna T, Farouni R, Conway T, Macpherson AJ, Platt RP. Noninvasive assessment of gut function using transcriptional recording sentinel cells. Science. 2022; 376, eabm6038.

Sonnenborn U. Escherichia coli strain Nissle 1917-from bench to bedside and back: history of a special Escherichia coli strain with probiotic properties. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2016 Oct; 363(19):fnw212.

Adolfsen KJ, Callihan I, Monahan CE, Greisen P, Spoonamore J, Momin M, Fitch LE, Castillo MJ, Weng L, Renaud L, Weile CJ, Konieczka JH, Mirabella T, Abin-Fuentes A, Lawrence AG & Isabella VM. Improvement of a synthetic live bacterial therapeutic for phenylketonuria with biosensor-enabled enzyme engineering. Nature Communications. 2021; 12, 6215.