Do bacteria remember? From an E. coli perspective

By Killian Scanlon

What if memory didn’t start with neurons? What if the origins of memory began with one of the most ancient organisms on earth? Bacteria. What’s to say these seemingly unintelligent microscopic beings haven’t been learning for the past few million years? In our most recent paper published in Nature Microbiology titled “Exploring the concept of bacterial memory”, we challenge this assumption. Memory is typically defined as “the faculty by which the mind stores and remembers information”. However, a broader definition has been proposed to encompass memories that can be stored outside the brain (1). Memory, at its core, is the encoding, storage and retrieval of information. These processes also occur in many non-neural organisms, including bacteria, plants and immune cells, but such examples fall outside the cognitive definition.

How can bacteria remember the past?

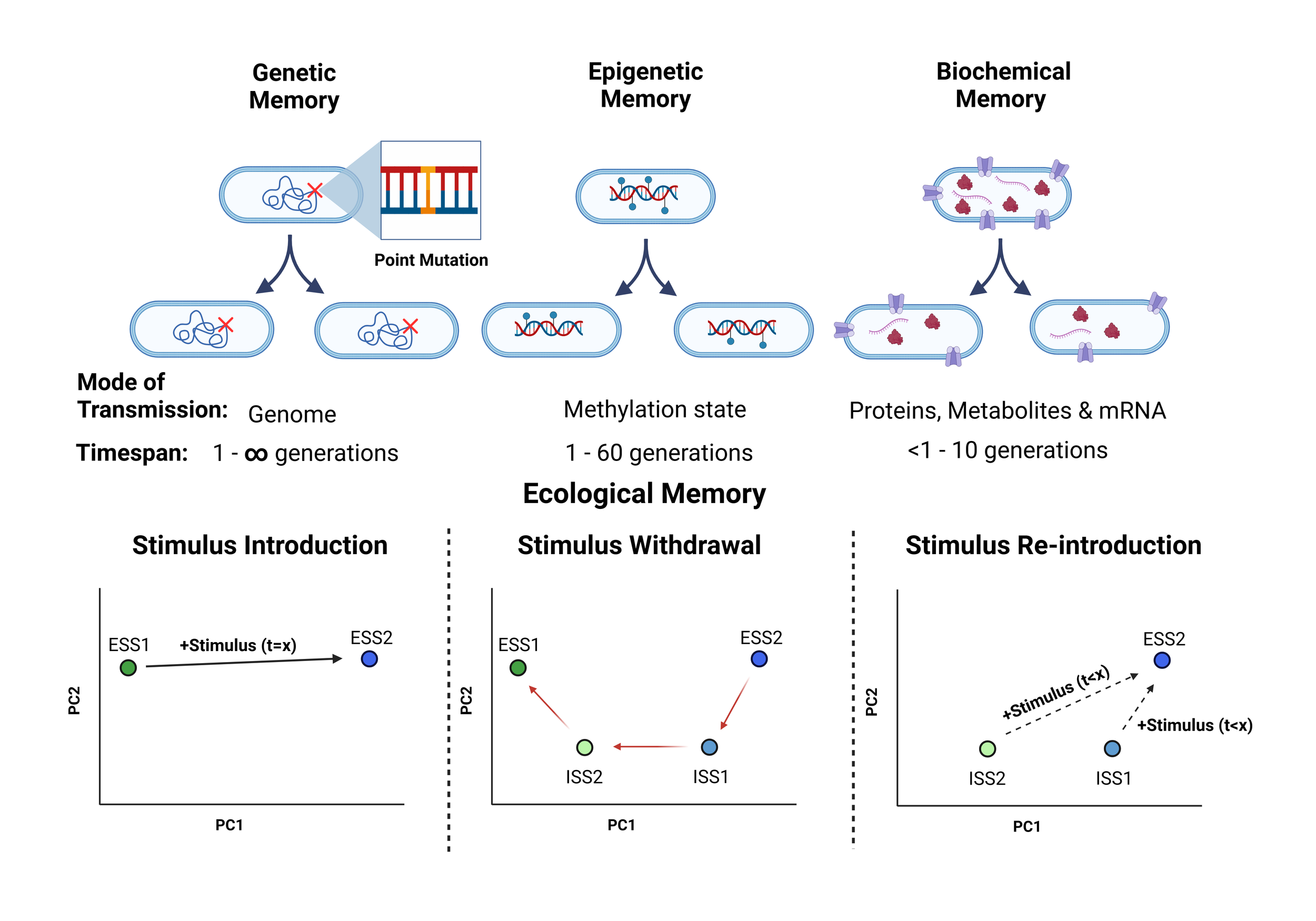

Memory storage systems in bacteria are obviously fundamentally different to animals with a brain. We propose that bacteria can store, inherit and retrieve multigenerational memories at the genetic, epigenetic and biochemical levels (Fig.1). Additionally, we suggest that microbial communities can store ecological memories through lasting population shifts (Fig. 1).

Fig.1: Bacterial memory inheritance found at genetic, epigenetic and biochemical levels. Genetic memory are long-term memories stored in the DNA sequence but can be altered by mutations or the uptake of new genetic material. Epigenetic memories are passed on through methylated DNA, which the daughter cell inherits half of from the parent cell. Biochemical memories are inherited through proteins, metabolites and mRNA. Ecological memory occurs at the community level, in which past environments can influences future community responses. We suggest that after stimulus withdrawal microbiota may shift back to the original composition Ecological Stable State 1 (ESS1) but can occupy intermediate stable states (ISS) on the recovery trajectory, which may allow a faster shift back to ESS2 if the stimulus is re-introduced at this point. The composition and trajectory of the microbiota are shaped by past exposures, not just the current environment. Adapted from (2). Image made in Biorender.com.

Anticipatory regulation

To illustrate bacterial memory, consider the journey of an E. coli transitioning from a soil environment to colonising a human gut. In the environment, the timing of some stimuli can be quite predictable or follow a predictable order. Some examples would be the predictable order of sugars distributed throughout the intestinal tract, depletion of glucose leading to a shift to secondary sugar use and bacteriophage binding to surface receptors leading to bacteriophage infection. Prediction and preparation for these future environments can provide fitness advantages in competitive ecosystems.

For the sake of the story, imagine E. coli living in the soil environment managed to hitch a ride on a farmer’s hand as he was harvesting his crops. He didn’t wash his hands before eating lunch, so some of the E. coli entered his mouth! E. coli have been colonising and passing through the human gut for thousands of years. So, upon entering the human mouth, the temperature rise (37°C) signals to the E. coli that they are in the mammalian host. E. coli can use this signal as a cue to pre-emptively shift to anaerobic respiration, to prepare for the drop in oxygen levels that awaits them as they pass through the host digestive tract (3). This phenomenon is known as anticipatory regulation, and many instances have been observed in E. coli (3–6). Oxygen and temperature levels are two independent stimuli, yet these two unrelated pathways can become linked through natural selection.

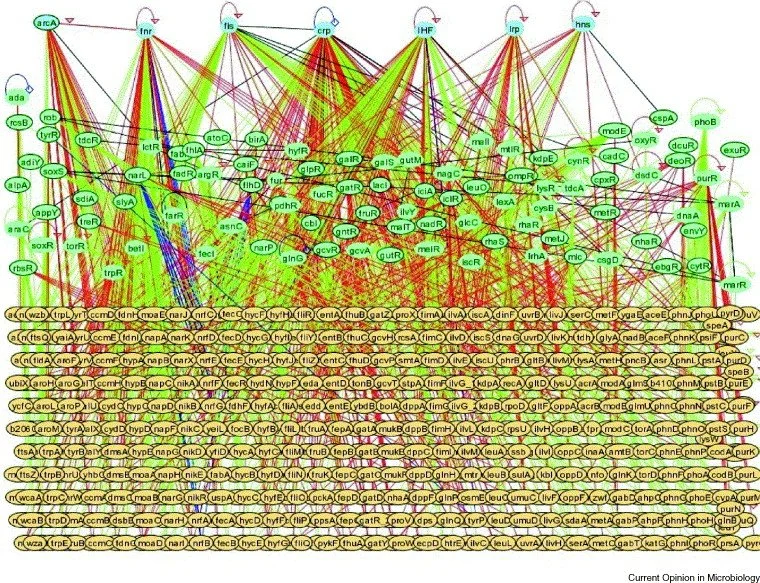

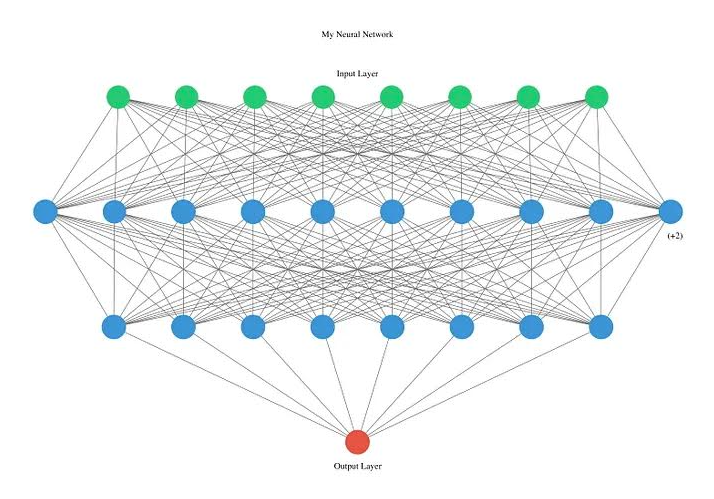

In a sense, anticipatory regulation resembles Pavlovian conditioning. Just like how dogs can learn to associate the bell with food, bacteria can associate one stimulus (temperature) to a second independent stimulus (drop in oxygen). Unlike mammals, this “learning” occurs over the course of hundreds to thousands of generations (5). One of the ways this appears to occur is through mutations in master regulators, which are proteins that control the expression of many genes at once (Blue nodes Fig.2). Even a small number of mutations in global regulators can have a large effect by altering DNA binding sites, potentially leading unrelated pathways to be linked (4). What’s interesting is that when you compare bacterial regulatory networks to neural networks, they look quite similar (Fig.2 & 3). In mammals, conditioning is believed to occur through a process called long-term potentiation, in which connections between neurons that “fire together wire together”. Similarly, in bacteria, new or stronger regulatory connections can be formed between unrelated stimuli if they are continually encountered together.

Chemotaxis memory

Only a very small percentage of the E. coli managed survive the stomach with some help of the pH buffering from lunch! At this stage, the remaining E. coli need to go in search of food to survive; they can use chemotaxis to help with this. Bacteria move using their propeller-like flagellum, which helps them move towards chemical attractants like food and away from repellents. What’s interesting is E. coli are so small they cannot measure if they are moving towards improving conditions directly, so they must use a form of short-term memory to help. They do this through the methylation state of their chemoreceptors; addition or removal of methyl groups on these chemoreceptors allows concentrations to be compared from a few seconds to minutes ago (9,10). These receptors help E. coli sense whether a chemical gradient is increasing or decreasing, rather than how much is present overall, a phenomenon known as logarithmic sensing (11).

Fig.2: Transcriptional regulatory network in E. coli. Transcription factors regarded as global regulators are shown as blue ovals, which control many regulated genes (yellow ovals) and other transcription factors are green ovals. Image from Current Opinion in Microbiology (7).

Fig. 3: Representation of a neural network. Image From Medium.com (8).

Biochemical memory

Using chemotaxis, the transiting E. coli have tracked down a nice source of the sugar lactose in the small intestine. It can take some time for the cell to become fully induced or respond upon lactose exposure, this is known as response lag. Often in the environment, nutrients are only sporadically available, so it’s often beneficial if bacteria are prepared for re-exposure to avoid that long response lag again. There are two main ways in which memories of prior nutrient exposure can be stored. The first one is response memory, which can occur in regulatory networks or feedback loops like the lac operon. When lactose is no longer available, the lac operon remains on as long as the residual inducer (allolactose) remains bound to the repressor, this typically lasts less than <1 generation (12). The second longer-lasting memory storage mechanism is through biochemical inheritance. During cell division many of the cytoplasmic contents are inherited, and this creates a memory effect in daughter cells. In E. coli inheritance of these stable intercellular proteins can reduce response lag and appears to have an effect up to 10 generations (12). These memory storage mechanisms improve the fitness of the bacteria in environments with sporadic nutrient availability.

Ecological Memory: How the past influences the present gut microbiota composition

Fast forward to a few months down the line, and our E. coli has established itself as a resident member in the Farmer’s gut microbiota. We suggest that the gut microbiota itself can store memories of past environments through lasting community shifts, such as lasting microbiota composition of a previous diet. Therefore, the present microbiota composition is also determined by the past, this is known as hysteresis, where a system’s state depends on its history.

During the first few months of E. coli colonisation, the farmer was eating a high-fat diet which favoured E. coli and allowed it to become a dominant member of the gut microbiota. However, recently the farmer switched to a lower-fat, high-fibre diet. What’s been observed in a mouse study is that members that favour the HFD, like the E. coli for example, can be reduced in abundance when the mice have returned to a healthy weight through dieting but many of the gut taxa do not return to pre-obesity levels (13). The gut microbiota can appear in a stable intermediate composition between the two diets, taking many more weeks of dieting to return to pre-obesity composition even after weight loss (13). This ecological memory of the previous diet plays a significant role in how the microbiome responds to future environmental changes. From an evolutionary perspective, ecological memory may be beneficial for maintaining gut compositional and metabolic balance by avoiding large and frequent compositional shifts.

What does the future hold?

Bacteria can use memory at multiple stages of their lifespan; this is an emerging area of research with many knowledge gaps. They can store memories through the inheritance of mutations, proteins/metabolites, methylation patterns and population shifts. It’s interesting that these non-neural cells demonstrate cognitive-like behaviour, possibly giving insights into the origins of cognitive memory. A deeper understanding of these forms of memory might aid in predictive microbiome/ecosystem modelling, conditioning strains for beneficial traits, among many other potential applications.

If you are interested, you can read the perspective here!

References

Zlotnik G, Vansintjan A. Memory: An Extended Definition. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2523.

Scanlon K, Shanahan F, Ross RP, Hill C. Exploring the concept of bacterial memory. Nat Microbiol. 2025 Nov 14;10(12):3049–58.

Tagkopoulos I, Liu YC, Tavazoie S. Predictive Behavior Within Microbial Genetic Networks. Science (1979). 2008 Jun 6;320(5881):1313–7.

Mahilkar A, Venkataraman P, Mall A, Saini S. Experimental Evolution of Anticipatory Regulation in Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol. 2022 Jan 11;12.

Rai N, Kim M, Tagkopoulos I. Understanding the Formation and Mechanism of Anticipatory Responses in Escherichia coli. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 May 26;23(11):5985.

Mitchell A, Romano GH, Groisman B, Yona A, Dekel E, Kupiec M, et al. Adaptive prediction of environmental changes by microorganisms. Nature. 2009 Jul 17;460(7252):220–4.

Martı́nez-Antonio A, Collado-Vides J. Identifying global regulators in transcriptional regulatory networks in bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003 Oct;6(5):482–9.

Adesh Shah. Medium.com. 2018. Visualizing Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) with just One Line of Code.

Macnab RM, Koshland DE. The Gradient-Sensing Mechanism in Bacterial Chemotaxis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1972 Sep;69(9):2509–12.

Sourjik V, Wingreen NS. Responding to chemical gradients: bacterial chemotaxis. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012 Apr;24(2):262–8.

Kalinin Y V., Jiang L, Tu Y, Wu M. Logarithmic Sensing in Escherichia coli Bacterial Chemotaxis. Biophys J. 2009 Mar;96(6):2439–48.

Correction: Memory and Fitness Optimization of Bacteria under Fluctuating Environments. PLoS Genet. 2014 Oct 16;10(10):e1004793.

Thaiss CA, Itav S, Rothschild D, Meijer MT, Levy M, Moresi C, et al. Persistent microbiome alterations modulate the rate of post-dieting weight regain. Nature. 2016 Dec 24;540(7634):544–51.